Ⅰ. Introduction

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) is a significant side effect associated with the administration of bone-modifying agents (BMAs) in the treatment of osteoporosis and osseous malignancies, both primary and metastatic.1 First described in 2003, MRONJ has since been recognized as a notable complication of BMA therapy.2 The condition is characterized by the presence of exposed necrotic bone in the maxillofacial region following dentoalveolar procedures in patients receiving BMA treatment, resulting in substantial impairment of quality of life.1 The etiology and pathophysiological mechanisms of MRONJ remain incompletely understood. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain its pathogenesis, including direct medication-induced cytotoxicity, compromised bone vascularity resulting in ischemic changes, dysregulation of host immune responses to oral microbiota, and impairment of physiological tissue repair processes in the oral cavity.3,4,5

Dental implants have recently been regarded as the gold standard for tooth replacement. Consequently, there has been an increase in implant procedures among patients receiving BMAs, raising concerns about the risk of MRONJ in this population.6,7 Generally, dental implant surgery during or after BMA administration is considered a major potential risk factor for MRONJ.1,8 Nevertheless, recent studies have indicated that dental implants placed before the initiation of BMA therapy may also be a risk factor for MRONJ. Some studies have reported higher incidence rates of MRONJ in these cases than in cases with implants placed during or after BMA administration.9,10

The impact of the timing of BMA administration and implant placement on the occurrence of MRONJ remains controversial. Moreover, there is a lack of comprehensive research evaluating the influence of local factors such as peri-implantitis, extraction of adjacent teeth, and surgical trauma on the occurrence and progression of MRONJ.

Therefore, we:

1. Retrospectively analyzed the timing of BMA administration, implant placement, and the onset of MRONJ to examine the factors influencing the occurrence of MRONJ at each stage.

2. Studied the effects of local factors, including peri-implantitis, adjacent tooth extraction, surgical trauma, and resultant local inflammation, on MRONJ occurrence.

We aimed to provide improved guidelines for implant surgery in patients receiving BMA therapy and contribute to the development of effective MRONJ prevention and treatment strategies.

Ⅱ. Material and Methods

This study retrospectively analyzed 38 patients who had a history of BMA administration and developed MRONJ around dental implants among those who visited the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Asan Medical Center between April 2008 and March 2024. The diagnosis and staging of MRONJ in these patients were determined according to the case definition outlined in the 2022 Position Paper of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS).1

We investigated the primary disease, type and method of BMA administration, duration of BMA therapy, and location of MRONJ occurrence. The chronological relationship between the timing of implant placement and BMA administration as well as the timing of MRONJ occurrence was investigated. In cases where MRONJ developed in implants placed after BMA administration, the time from implant surgery to the onset of MRONJ was examined to assess the direct impact of surgery. In contrast, for implants placed before BMA administration, the period until MRONJ onset was not measured, assuming that sufficient osteointegration had occurred postoperatively. Based on these findings, patients were divided into three groups.

- Group 1: patients who developed MRONJ around implants, which were placed before BMA therapy

- Group 2: patients who developed MRONJ around the implants within one year after implant placement following BMA therapy

- Group 3: patients who developed MRONJ around the implants more than one year after implant placement following BMA therapy

We investigated the primary causes of MRONJ and classified them into two main categories: chronic inflammation(peri-implantitis) and acute inflammation (trauma caused by surgery or tooth extraction). Peri-implantitis was diagnosed based on inflammatory changes around the implant and alveolar bone loss observed on panoramic radiography and clinical findings. Trauma was defined as the occurrence of MRONJ without signs of peri-implantitis on panoramic radiographs or clinical images, regardless of the timing of BMA administration, and was attributed to surgical procedures or tooth extraction.

A cross-analysis was conducted to investigate the relationship between the timing of MRONJ occurrence and the causes of MRONJ using the groups defined above.

Additionally, we examined the occurrence of MRONJ in other areas of the oral cavity (such as natural teeth or edentulous regions) beyond the affected implants.

Ⅲ. Results

All 38 patients were female, with 37 cases of osteoporosis as the primary disease and one case of breast cancer. Upon investigating the types and routes of BMA administration, 15 cases involved oral bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate, and zoledronate), 7 cases involved intravenous bisphosphonates, and 1 case involved both oral and intravenous bisphosphonates. There were three cases in which denosumab was administered intravenously as monotherapy and 12 cases in which both bisphosphonates and denosumab were administered concurrently.

As a result of investigating the relationship between the timing of BMA administration, implant placement, and MRONJ occurrence for a total of 38 subjects, out of 38 cases, group 1 accounted for 21 cases (55.3%), group 2 for 9 cases (23.7%), and group 3 for 8 cases (21.0%).

Analysis of the primary causes of MRONJ revealed that peri-implantitis was observed around the affected implants in 26 patients (68.4%), whereas alveolar bone trauma, such as implant surgery or tooth extraction, was identified as the primary cause in 12 patients (31.6%). Among these cases, tooth extraction was identified as the direct cause in four cases, with two cases in Group 1 and two cases in Group 3.

An investigation into whether MRONJ occurred in other areas of the oral cavity besides the affected implants revealed that in nine cases, MRONJ was observed in other natural teeth or edentulous areas. Additionally, there were 5 cases in which implants were placed simultaneously with MRONJ-affected implants, but these showed normal osteointegration.

The results are summarized in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

Cross-analysis was performed to examine the relationship between the timing of MRONJ occurrence and the causes of MRONJ. As the expected frequency of less than 5 accounted for 33.3% of all cells, Fisher's exact test was used to determine the significance level instead of Pearson's chi-square test. Fisher's exact test resulted in p < 0.001, indicating a statistically significant relationship between the timing of MRONJ occurrence and causes of MRONJ (Table 4).

Table 1.

Information about group 1

| No. | Age | Sex | Indication | Medication | Site of Implant | MRONJ stage | Cause of MRONJ |

MRONJ on another place |

| 1 | 73 | Female | Osteoporosis | Risedronate PO 35mg weekly for 3 years | #35i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 2 | 69 | Female | Osteoporosis | Denosumab IV 60mg 6 monthly (unknown duration) | #14i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 3 | 76 | Female | Osteoporosis | Ibandronate IV 3mg 6 monthly for 1.5 years Denosumab IV 60mg One-off | #37i | stage 2 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 4 | 78 | Female | Osteoporosis | Ibandronate IV 3mg 3 monthly (unknown duration) | #25i, 26i | stage 2 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 5 | 76 | Female | Osteoporosis | Risedronate PO 150mg monthly for 3 years | #27i | stage 2 |

Trauma (Tooth extraction) | #26 socket area |

| 6 | 81 | Female | Osteoporosis | Denosumab IV 60mg 6 monthly for 4 years Risedronate PO 35mg weekly for 5 years | #45i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | #46 |

| 7 | 80 | Female | Breast cancer | Risedronate PO 150mg monthly for 5.5 years | #45i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 8 | 65 | Female | Osteoporosis | Zoledronate IV 5mg 6 monthly for 4 years | #47i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 9 | 81 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 3.5 years | #46i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 10 | 76 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 5 years Denosumab IV 60mg 6 monthly for 2 years | #37i | stage 2 | Trauma (Tooth extraction) | #36 socket area |

| 11 | 82 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 2 years | #43i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 12 | 72 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 10mg daily for 3 years | #11i, 13i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None* |

| 13 | 81 | Female | Osteoporosis | Zoledronate IV 5mg yearly for 2 years | #14i, 15i, 16i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None* |

| 14 | 77 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 2 years Denosumab IV 60mg 6 monthly for 2 years | #36i, 37i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 15 | 75 | Female | Osteoporosis | Risedronate PO 35mg weekly for 2 years | #44i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 16 | 72 | Female | Osteoporosis | Denosumab IV 60mg 6 monthly for 1.5 years | #26i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 17 | 73 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 1.5 years | #25i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 18 | 72 | Female | Osteoporosis | unknown BP IV 6 monthly for 2.5 years | #14i, 25i, 26i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 19 | 76 | Female | Osteoporosis | unknown BPPO monthly for 6 months | #37i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 20 | 68 | Female | Osteoporosis | unknown BPPO monthly for 3 years Denosumab IV 60mg One-off | #16i | stage 2 | Peri-implantitis | None |

| 21 | 74 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 2 years | #36i, 37i | stage 2 | Peri-implantitis | None |

Table 2.

Information about group 2

| No. | Age | Sex | Indication | Medication before implant placement | Drug holiday | Site of Implant | MRONJ stage | Cause of MRONJ | Time to onset of MRONJ after surgery | MRONJ on another place |

| 1 | 81 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 7 years Zoledronate IV 5mg One-off Denosumab IV 60mg 6 monthly for 1.5 years | 6 month (Denosumab IV) | #23i, 24i, 26i, 27i | stage 1 | Trauma | 6 months | None* |

| 2 | 82 | Female | Osteoporosis | Zoledronate IV 5mg yearly for 2 years | no drug holiday | #36i, 37i | stage 2 | Peri-implantitis | 8 months | None* |

| 3 | 75 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 20 years Denosumab IV 60mg 6 monthly for 1 years | no drug holiday | #25i, 34i, 36i | stage 1 | #25i: Trauma #34i, 46i: Peri-implantitis | 9 months | None* |

| 4 | 64 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 4 years | unknown | #14i, 15i, 16i | stage 1 | Trauma | 2 months | None |

| 5 | 70 | Female | Osteoporosis | Zoledronate IV 4mg monthly for 2 years | no drug holiday | #46i | stage 1 | Trauma | 4 months | #44, 45 |

| 6 | 78 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 10mg daily for 6 years | no drug holiday | #31i | stage 1 | Trauma | 10 months | #42, 43 |

| 7 | 85 | Female | Osteoporosis | Denosumab IV 60mg 6 monthly for 4 years | no drug holiday | #34i, 36i | stage 1 | Trauma | 2 months | None |

| 8 | 75 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 4 years Ibandronate IV 3mg 6 monthly for 1.5 years | 1 year (Ibandronate IV) | #36i, 37i | stage 1 | Trauma | 2 months | None |

| 9 | 67 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 2 years | unknown | #17i | stage 1 | Trauma | 9 months | None |

Table 3.

Information about group 3

| No. | Age | Sex | Indication | Medication before implant placement | Drug holiday | Site of Implant | MRONJ stage | Cause of MRONJ | Time to onset of MRONJ after surgery | MRONJ on another place |

| 1 | 70 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 14 weeks Zoledronate IV 5mg 6 monthly for 2 years Denosumab IV 60mg One-off |

3 months (Alendronate PO) Restart 1 year after OP | #16i | stage 2 | Peri-implantitis | 3.5 years | #15 |

| 2 | 68 | Female | Osteoporosis | Zoledronate IV 5mg 6 monthly for 2 years | unknown | #27i | stage 2 | Peri-implantitis | 4 years | None |

| 3 | 82 | Female | Osteoporosis | Risedronate PO 150mg monthly for 7 years | unknown | #45i, 46i, 47i | stage 2 | Peri-implantitis | More than 1 year | None |

| 4 | 78 | Female | Osteoporosis | Ibandronate PO 150mg monthly for 3 months Ibandronate IV 3mg 3 monthly for 6 years Zoledronate IV 5mg yearly for 2 years Denosumab IV 60mg 6 monthly for 2.5 years | no drug holiday | #26i, 36i, 46i, 47i | stage 2 |

#36i: Trauma (Tooth extraction) #26i, 46i, 47i: Peri-implantitis | 5 years | #37 socket, #26i, 46i, 47i |

| 5 | 70 | Female | Osteoporosis | Risedronate PO 35mg weekly (unknown duration) Denosumab IV 60mg 6 monthly for 2 years | no drug holiday | #46i.47i | stage 2 | Trauma (Tooth extraction) | More than 1 year | #45 socket |

| 6 | 77 | Female | Osteoporosis | Alendronate PO 10mg daily for 1.5 years Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 3 years Ibandronate IV 3mg 6 monthly for 3 years | no drug holiday | #13i | stage 2 | Peri-implantitis | 6 years | None |

| 7 | 74 | Female | Osteoporosis | unknown BPPO monthly for 7 years Denosumab IV 60mg 6 monthly for 3 years | unknown | #46i, 47i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | More than 1 year | #45, 48 |

| 8 | 78 | Female | Osteoporosis | Risedronate PO 35mg weekly for 1 year Alendronate PO 70mg weekly for 2.5 years | no drug holiday | #24i, 25i, 26i | stage 1 | Peri-implantitis | 1.5 years | None |

Table 4.

The correlation between the timing of MRONJ occurrence and its direct causes

|

Acute inflammation (Trauma - extraction, surgery) |

Chronic inflammation (peri-implantitis) | Total | Fisher’s exact test (p) | |

| Group 1 |

2 (9.5%) |

19 (90.5%) |

21 (100.0%) | <0.001 |

| Group 2 |

8 (88.9%) |

1 (11.1%) |

9 (100.0%) | |

| Group 3 |

2 (25.0%) |

6 (75.0%) |

8 (100.0%) | |

| Total |

12 (31.6%) |

26 (68.4%) |

38 (100.0%) |

Ⅳ. Discussion

Previous studies investigated the risk of MRONJ around implants with respect to the timing of BMA administration and implant placement. In the study by Giovannacci et al., a total of 27 cases of MRONJ around implants were analyzed, of which 15 cases (55.6%) occurred in implants placed before BMA administration, and 12 cases (44.4%) occurred in implants placed after BMA administration.11 In the study by Kwon et al., 19 cases of MRONJ were analyzed, and only 3 patients (15.8%) were found to have developed MRONJ due to implant surgery-related trauma in implants placed after BMA administration.12 In the study by Lazarovici et al., 27 cases of MRONJ were analyzed, with 22 cases (81.5%) occurring in implants placed before BMA administration and 5 cases (18.5%) occurring in implants placed after BMA administration.13 In the systematic review by Matsuo et al., 18 studies were analyzed, and while there was a tendency for a higher risk of MRONJ in implants placed before BMA administration, the difference was not statistically significant.10 In summary, the conclusions of these studies generally suggest a higher tendency for MRONJ to occur in implants placed before BMA administration, though no statistically significant difference was found.

In this study, like previous studies, we analyzed the relationship between the timing of BMA administration and the placement of implants where MRONJ occurred. Twenty-one cases (group 1, 55.3%) of MRONJ occurred in implants placed before BMA administration, which was relatively higher than in cases with implants placed after BMA administration. Among the 38 cases, 17 cases (group 2, 3, 44.7%) of MRONJ occurred in implants placed after BMA administration, and of these, nine (group 2, 23.7%) developed MRONJ within one year of implant placement. Based on these results, the risk of MRONJ in relation to the chronological order of BMA administration and implant placement did not significantly differ from the findings of previous studies.

Fisher's exact test showed a statistically significant correlation between the timing of MRONJ and its direct causes. In groups 1 and 3, 19 patients (90.5%) and 6 patients (75.0%) developed MRONJ due to chronic inflammation (peri-implantitis). This suggests that MRONJ occurred in implants with completed osseointegration, that is, implants placed more than one year ago, and was primarily caused by chronic inflammatory conditions around the implants. In contrast, in Group 2, eight cases (88.9%) occurred due to acute inflammation. This suggests that in MRONJ cases occurring within one year of implant placement following BMA administration, the main cause was acute inflammation resulting from surgical trauma or the initial osseointegration process.

In 12 cases (31.6%), signs of peri-implantitis, such as alveolar bone loss, were not observed around the implants where MRONJ occurred. Of these, eight cases in Group 2 appeared to have been primarily caused by acute inflammation due to surgical trauma, and in all eight cases, MRONJ was classified as stage 1, indicating a relatively lower degree of lesion progression. Of these eight cases, six involved patients who had been on long-term BMA therapy for over four years, which aligns with previous studies suggesting that patients receiving BMA for more than four years are at an increased risk of MRONJ following implant surgery.4

In 4 cases (10.5%), extraction of the teeth adjacent to the implant was the primary cause of MRONJ. Of these, two cases involved implants placed before BMA administration, and two cases involved implants placed after BMA administration. In both cases where the implants were placed after BMA administration, MRONJ occurred more than one year after implant placement. Because no signs of peri-implantitis were observed around the implants on panoramic radiographs or clinical findings before the extractions in all four cases, it can be concluded that extraction of the adjacent teeth was the primary cause of MRONJ.

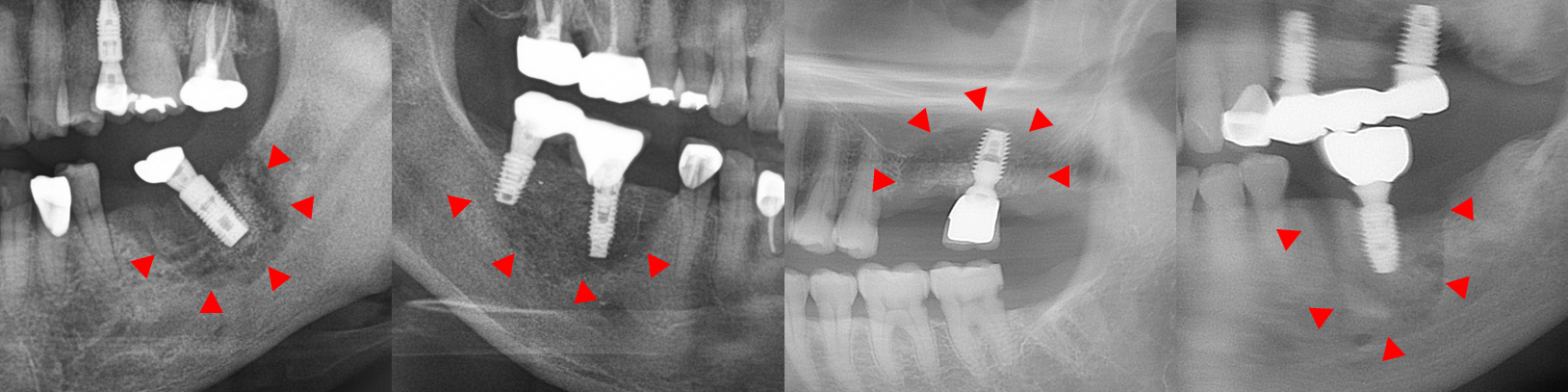

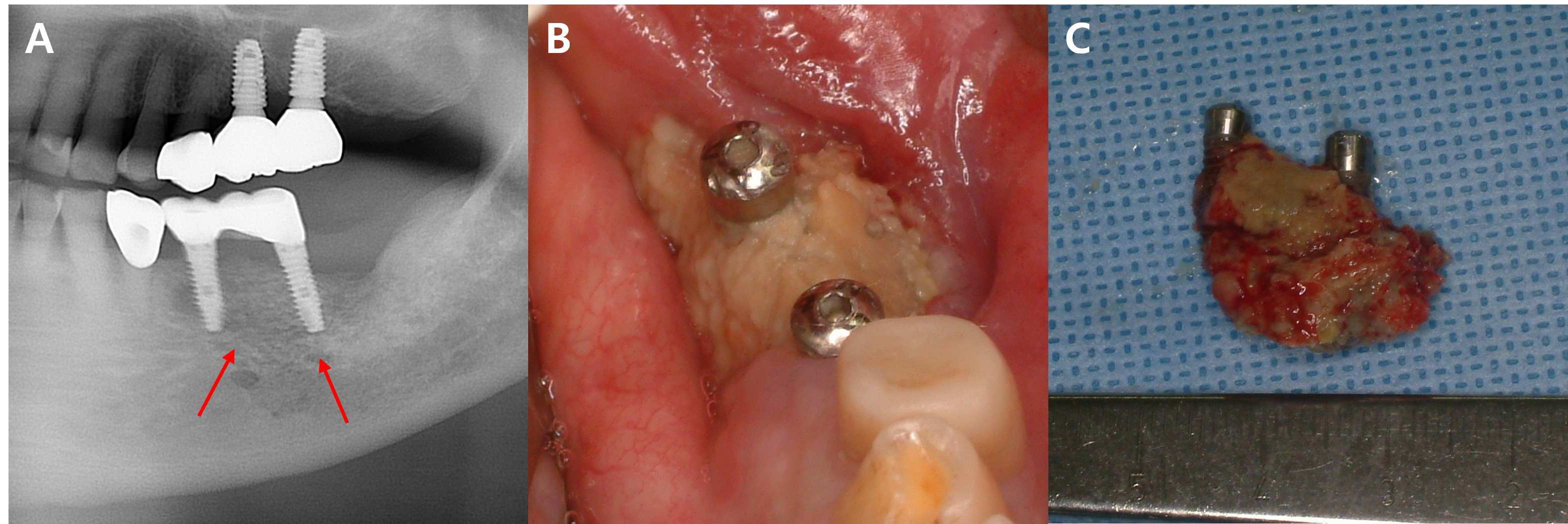

Notably, when teeth adjacent to the implants were extracted, more extensive areas of necrotic bone were observed compared with MRONJ caused by other factors (Fig. 1). The following potential causes could be considered for this observation. First, in cases of tooth extraction, there was likely preexisting chronic inflammation in the surrounding area due to periodontitis or infection, which necessitated extraction. This chronic inflammation, combined with acute inflammation from the trauma of extraction, could lead to more severe inflammatory changes in the tissues surrounding the adjacent implant. This heightened inflammatory environment may spread and result in more extensive MRONJ, affecting both the adjacent implant and surrounding areas.14 Secondly, BMA, such as bisphosphonates, have a high affinity for bone minerals and strongly bind to hydroxyapatite. Because of this property, they accumulate in high concentrations in areas where active bone remodeling occurs.15 An extraction socket is an area where bone remodeling is highly active, making it more likely to be exposed to higher concentrations of anti-resorptive agents compared to other cases, potentially affecting the tissues around adjacent implants. Third, unlike implant surgeries in which the site is protected by sutures, the extraction socket remains temporarily exposed to the external environment, making it more susceptible to infection. Such infections are a significant risk factor for MRONJ and can lead to inflammatory changes in the tissues around the adjacent implants. Recent studies suggest that explaining MRONJ solely by reduced bone turnover caused by medication is insufficient and that infection may play a key role.16

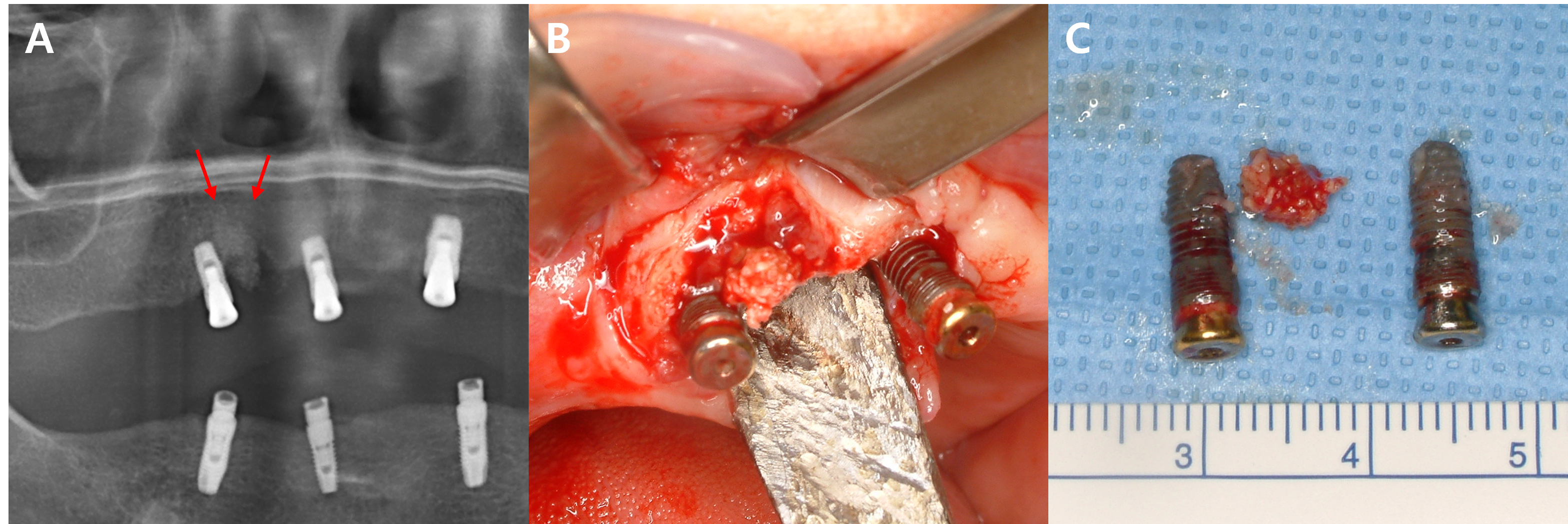

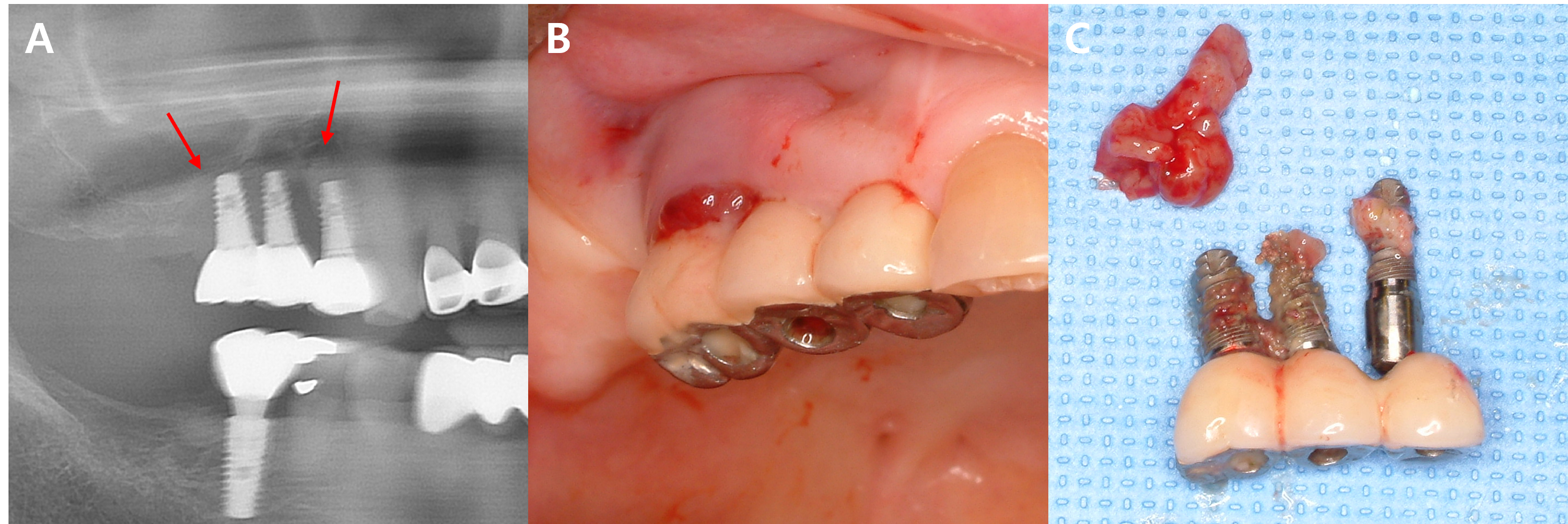

In this study, five patients with multiple implants placed across several quadrants at similar times developed MRONJ. In all five cases, MRONJ did not occur extensively across multiple implants in different quadrants but rather presented as localized inflammation in a single quadrant. This pattern of MRONJ suggests that specific factors causing localized inflammation (such as the design of dental prostheses prone to peri-implantitis) may have a greater impact on the development of MRONJ around the implants than the overall changes in the oral environment. A common feature among these five cases was that MRONJ occurred around implants near the bridge pontics, which are relatively more difficult to maintain in terms of oral hygiene (Figs. 2, 3, and 4).

Fig. 4.

MRONJ occurring around the prosthesis connected to adjacent implants in the right maxillary posterior region. (A, B) Progressive bone loss and necrotic bone (arrow) are observed on the panoramic X-ray, and localized inflammation is seen around the exposed bone on the buccal side in the clinical photo, (C) Inflammatory tissue and implants removed through surgery. Sequestrum is observed attached to the removed implants.

This study had several limitations. First, the study population was limited to 38 female patients, which did not allow us to account for sex differences, and the small sample size limited the generalizability of the results. Second, since osteoporosis was the cause of BMA administration in all but one case, there was insufficient analysis of patients receiving BMA for other reasons, such as cancer. This limits the ability to assess the differences in MRONJ risk based on the various causes of BMA administration. Third, while we interpreted MRONJ that developed within one year of implant placement after BMA administration as being related to surgical trauma, we did not sufficiently consider the impact of microdamage and mechanical stress from implant loading, which has been suggested in recent studies.17 This may limit the accuracy of interpreting the causes of MRONJ. Fourth, although we identified inflammation around the implant as an important factor in the development of MRONJ, we did not apply this method to quantitatively measure the degree of inflammation. As a result, there were limitations in accurately assessing the correlation between the severity of inflammation and risk of MRONJ. Finally, this was a retrospective study, which limited the ability to track changes over time or establish clear causality. These limitations highlight important aspects that should be addressed in future research and suggest the need for larger-scale prospective studies and long-term follow-up studies involving diverse patient groups.

Ⅴ. Conclusion

In this study, differences in the primary direct causes of MRONJ were observed, depending on the timing of BMA administration and implant placement. Chronic inflammation was identified as the main cause of MRONJ when osseointegration was completed (Groups 1 and 3), whereas acute inflammation was the predominant cause within one year after surgery (Group 2). Additionally, local infections and the spread of inflammation due to the extraction of adjacent teeth can lead to extensive lesions around the MRONJ site.

Therefore, to prevent MRONJ around dental implants, active management and resolution of the inflammatory environment surrounding the implants are considered effective. Regular oral examinations, thorough oral hygiene, and prompt response to early signs of inflammation appear to be effective strategies for the prevention and treatment of MRONJ.